Introduction of Public Debt

Public debt or borrowings are money raised on the security of consolidated fund of India and repayable out of it. In layman terms, public debt is the total amount borrowed by the government of a country.

But, Why government borrow?

- Budgetary deficits must be financed by either taxation or borrowing or printing money.

- Governments have mostly relied on borrowing, giving rise to what is called government debt.

- The concepts of deficits and debt are closely related. Deficits can be thought of as a flow which adds to the stock of debt.

- If the government continues to borrow year after year, it leads to the accumulation of debt and the government has to pay more and more by way of interest. These interest payments themselves contribute to the debt.

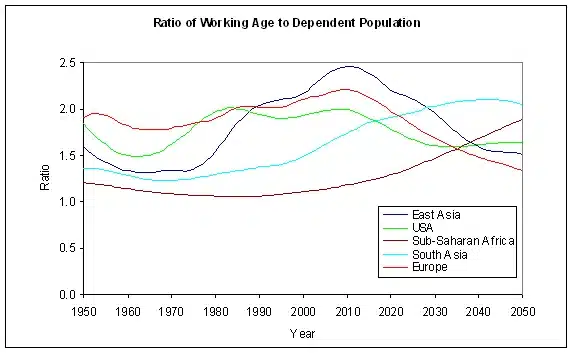

- By borrowing, the government transfers the burden of reduced consumption on future generations. This is because it borrows by issuing bonds to the people living at present but may decide to pay off the bonds some twenty years later by raising taxes.

- These may be levied on the young populations that have just entered the work force, whose disposable income will go down and hence consumption. Thus, national savings, it was argued, would fall. Also, government borrowing from the people reduces the savings available to the private sector. To the extent that this reduces capital formation and growth, debt acts as a ‘burden’ on future generations.

Sources of Public Debt

- Dated government securities or G-secs

- Treasury Bills or T-bills

- External Assistance

- Short term borrowings

Types of Borrowing:

(A). Internal Borrowing

- Money borrowed within the country from various sources and various instruments is called internal borrowing.

- Internal loans that make up for the bulk of public debt are further divided into two broad categories – marketable and non-marketable debt.

- Dated government securities (G-Secs) and treasury bills (T-bills) are issued through auctions and fall in the category of marketable debt. Intermediate treasury bills (with a maturity period of 14 days) issued to state governments and public sector banks, special securities issued to National Small Savings Fund (NSSF) are classified as non-marketable debt.

- Dated Securities: Popularly known as G-Secs (Government Securities), they are primarily issued by Centre as fixed coupon bonds of different maturities (short-, medium- and long-term). They are today the single-most important source of deficit financing (more than 90 per cent) for the Centre.

- Treasury Bills: T-Bills are zero coupon securities issued by the Centre at a discount and are redeemed at their face value at maturity. Issued for short-term (less than 365 days) today they have three tenures—91, 182 and 364 days.

- 14-Day T-Bills: These ‘non-transferable’ T-Bills (introduced by the RBI in 2013 to finance Centre’s ways and means advances as issuance of ‘on-tap’ treasury bills was phased out) are issued by the Centre to only States, foreign central banks and other specified bodies at an interest rate fixed at 3 per cent below the average yield of 91- days T-Bills in the preceding quarter.

- Securities issued to International Financial Institutions: Securities issued by Centre as India’s contributions to the international financial institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, Asian Development Bank, etc.

- Securities issued against ‘Small Savings’: The deposits under small savings scheme (SSSs) are credited to the NSSF (National Small Savings Fund) from which withdrawals also keep taking place. Rest of the fund (net withdrawals) of the NSSF is invested in special G-Secs issued by the Centre.

(B). External Borrowing

- External loans are not market loans. They have been raised from institutional creditors at concessional rates. Most of these external loans are fixed-rate loans, free from interest rate or currency volatility. This constitutes a variety of ‘multilateral’ and ‘bilateral’ loans from IMF, World Bank, ADB, Sovereign Funds, foreign governments, etc.

What is Debt-to-GDP ratio?

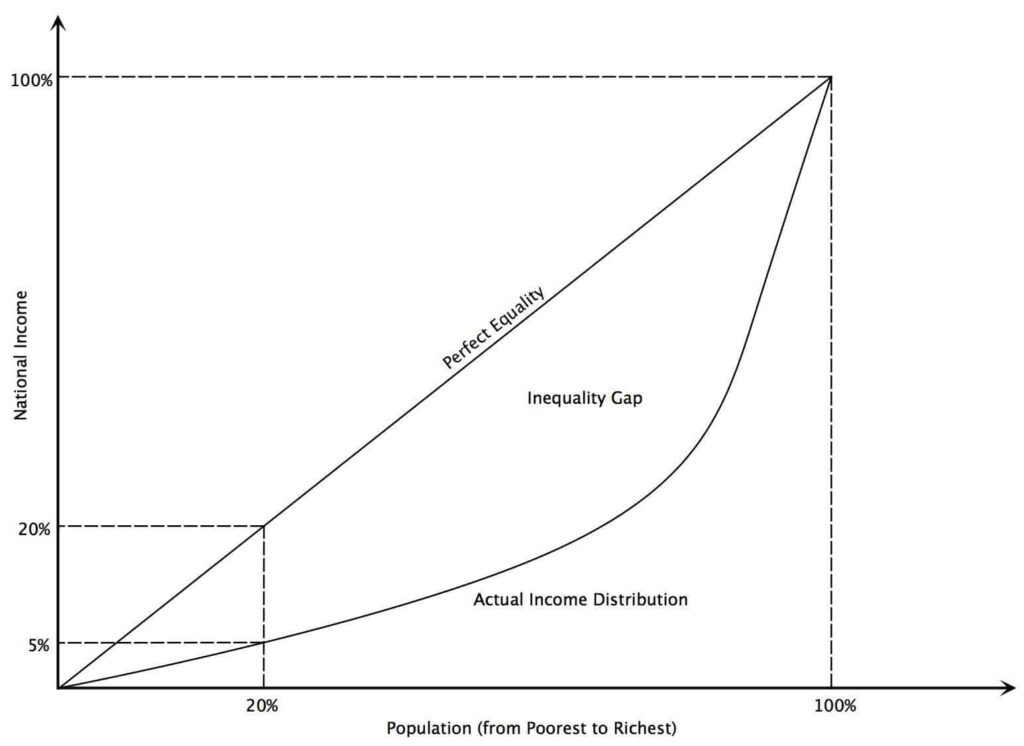

- The debt-to-GDP ratio indicates how likely the country can pay off its debt. Investors often look at the debt-to-GDP metric to assess the government’s ability of finance its debt. Higher debt-to-GDP ratios have fuelled economic crises worldwide.

Is there an acceptable level of debt-to-GDP?

- The NK Singh Committee on FRBM had envisaged a debt-to-GDP ratio of 40 per cent for the central government and 20 per cent for states aiming for a total of 60 per cent general government debt-to-GDP.

Importance of Public Debt Management in India

- As per Reserve Bank of India Act of 1934, the Reserve Bank is both the banker and public debt manager for the Union government.

- The RBI handles all the money, remittances, foreign exchange and banking transactions on behalf of the Government.

- The Union government also deposits its cash balance with the RBI. However, of late, there is a demand for creating a specialized agency for managing public debt as exists in some advanced economies. For instance, the Niti Aayog has advocated the creation of a separate public debt management agency (PDMA).

Public Debt versus Private Debt

- Public Debt is the money owed by the Union government, while private debt comprises of all the loans raised by private companies, corporate sector and individuals such as home loans, auto loans, personal loans.

Public Debt as a percentage of GDP

- The Union government’s liabilities account for a little over 46% of the country’s GDP. However, if the public debt is calculated as general government liabilities, which also includes the liabilities of states then it goes up to 68% of the country’s GDP.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increase in debt not only for India but for most countries around the world.

- Last year (in 2020), India’s debt was around ₹147 lakh crore against this year’s (in 2021) estimated GDP of ₹194 lakh crore . This year (in 2021), the government plans to borrow another ₹12 lakh crore.

- Most of the emerging economies have government debt that is around 40% to 50% of their GDP. Compared to that our debt is around 75% to 80% of our GDP, which used to be on the higher side.

- Advanced countries like the US and Japan may have even higher debt levels. But their repayment capacity is also much higher than India.

- The Indian government also has the option to flood the economy with more rupees to make its payments. If the government has too much debt and it fulfills this debt by printing more money, then the value of that money goes down.

- Right now we’re spending more to support the poor people but it goes beyond a certain limit, the same poor people are going to pay back in 10 years.

- Borrowing more money means that you’ll have to pay it back at some point of time. And, this isn’t the first time that India has found itself in this situation.

- During the Asian crisis we went from 67 to 83% when our growth rate was 3.9%. The economy was nothing. Then we had good growth and we came back to 66%.

- However, if there are unforeseen circumstances like another pandemic or a war have the potential in the near term, the growth may take a hit and that is when debt will become a problem.

Is public debt bad for the sovereign?

- No. But the government, like a typical household which takes loans when expenses are higher than the income, must have the capacity to repay the debt. Secondly, the debt must be for investment and capital format.

When Public Debt Is Good

- In the short run, public debt is a good way for countries to get extra funds to invest in their economic growth. Public debt is a safe way for foreigners to invest in a country’s growth by buying government bonds.

- This is much safer than foreign direct investment. That’s when foreigners purchase at least a 10% interest in the country’s companies, businesses, or real estate. It’s also less risky than investing in the country’s public companies via its stock market. Public debt is attractive to risk-averse investors since it is backed by the government itself.

When Public Debt Is Bad

- Governments tend to take on too much debt because the benefits make them popular with voters. Increasing the debt allows government leaders to increase spending without raising taxes.

- Investors usually measure the level of risk by comparing debt to a country’s total economic output, known as gross domestic product (GDP). The debt-to-GDP ratio gives an indication of how likely the country can pay off its debt.

- Investors usually don’t become concerned until the debt-to-GDP ratio reaches a critical level.

- When debt approaches a critical level, investors usually start demanding a higher interest rate. They want more return for the greater risk. If the country keeps spending, then its bonds may receive a lower rating. This indicates how likely it is that the country will default on its debt.

Also refer :