Mauryan Art And Architecture

Sixth century B.C. marks the beginning of new religious and social movements in the Gangetic valley in the form of Buddhism and Jainism (Sramana/Shraman Tradition). Magadha emerged as a powerful kingdom and consolidated its control over the other religions. It marked a significant shift in Indian art from the use of wood to stone.

- King Ashoka patronized the shraman tradition in the third century BCE.

- The shraman tradition refers to several Indian religious movements parallel to but separate from the historical vedic religion.

- It includes Jainism, Buddhism, and others such as Ajivikas, and Carvakas.

- Religious practices had many dimensions during this period.

- Worship of Yakshas and Mother Goddess was prevalent during that time.

- Yaksha worship was very popular before and after the advent of Buddhism and it was assimilated in Buddhism and Jainism.

- Construction of stupas and viharas (dwelling place of monks) became part of the Buddhist tradition.

- However, in this period, apart from stupas and viharas, stone pillars, rock cut caves and monumental figure sculptures were carved in several places.

Influence on Mauryan Art

- Religious influence

- Buddhism became most popular social & religious movement

- Concept of religious sculpture prominent

- Foreign Influence

- First three Mauryan emperors Chandragupta, Bindusara & Ashoka known to have friendly relations with Hellenistic west and Achamenian of Iran

- Adaptation of Achamenian Pillars and Palaces

Features of Mauryan Art and Architecture

By the fourth century BC, the Mauryas established their power in the Magadha region. By the third century BC, a large part of India was under Mauryan control.

- Mauryan art and architecture were a culmination of a long movement which began indigenously.

- Mauryan art was different from the earlier art traditions in that it departed from the use of wood, sun-dried brick, clay, ivory and metal to that of stone in huge dimensions.

- One of the important features of Mauryan art is its Achaemenid connection. Mauryan dominions under Chandragupta Maurya touched Afghanistan and what had been erstwhile Achaemenid possessions.

- Stambha architecture which had its beginning in wood, was transformed into a new medium, Stone. Gradually it acquired capitals and bases, with the shaft also becoming eight or sixteen-sided.

Classification of Mauryan Art and Architecture

- Mauryan architecture can be divided into Court Art and Popular Art.

- Court Art : Palaces, Pillars, Stupa, Caves

- Popular Art : Pottery, Sculpture

Mauryan Court Art

It implies architectural works (in the form of pillars, stupas and palaces) commissioned by Mauryan rulers for political as well as religious reasons.

Palaces

- The capital at Pataliputra and the palaces at Kumrahar were created to reflect the splendour of the Mauryan Empire.

- Greek historian, Megasthenes, described the palaces of the Mauryan empire as one of the greatest creations of mankind and Chinese traveler Fa Hien called Mauryan palaces as god gifted monuments.

- Persian Influence: The palace of Chandragupta Maurya was inspired by the Achaemenid palaces at Persepolis in Iran.

- Material Used: Wood was the principal building material used during the Mauryan Empire.

- Examples: The Mauryan capital at Pataliputra, Ashoka’s palace at Kumrahar, Chandragupta Maurya’s palace.

- About Pataliputra, Megasthenese mentions that towns were surrounded by wooden walls where a number of holes were created to let the arrow pass by.

- The town had 64 entrances and 570 towns.

- The royal assembly building in Kumhrar was a hall with 80 pillars. Its roof and floor were made of wood.

- The hall has been variously assigned as the palace of Asoka, the audience hall, the throne room of Mauryas, a pleasure hall, or the conference hall for the third Buddhist council held at Pataliputra in 3rd Century B.C. during the reign of Ahsoka.

- Patanjali also mentioned Chandragupta‟s Rajsabha in his Mahabhashya.

- Arrian (a Greek historian) compared Chandragupta‟s palace with the buildings of Susa and Ekbatan.

Pillars

During the reign of Ashoka, the inscription on pillars – as a symbol of the State or to commemorate battle victories – assumed great significance. He also used pillars to propagate imperial sermons as well. Examples: Lauria Nandangarh Pillar in Champaran, Sarnath Pillar near Varanasi, etc.

- Ashoka pillars, (On an average of 40 ft. height, usually made of chunar sandstone), as a symbol of the state, assumed a great significance in the entire Mauryan Empire.

- Objective: The main objective was to disseminate the Buddhist ideology and court orders in the entire Mauryan empire.

- Language: While most Ashoka pillar edicts were in Pali and Prakrit language, few were written in Greek or Aramaic language also.

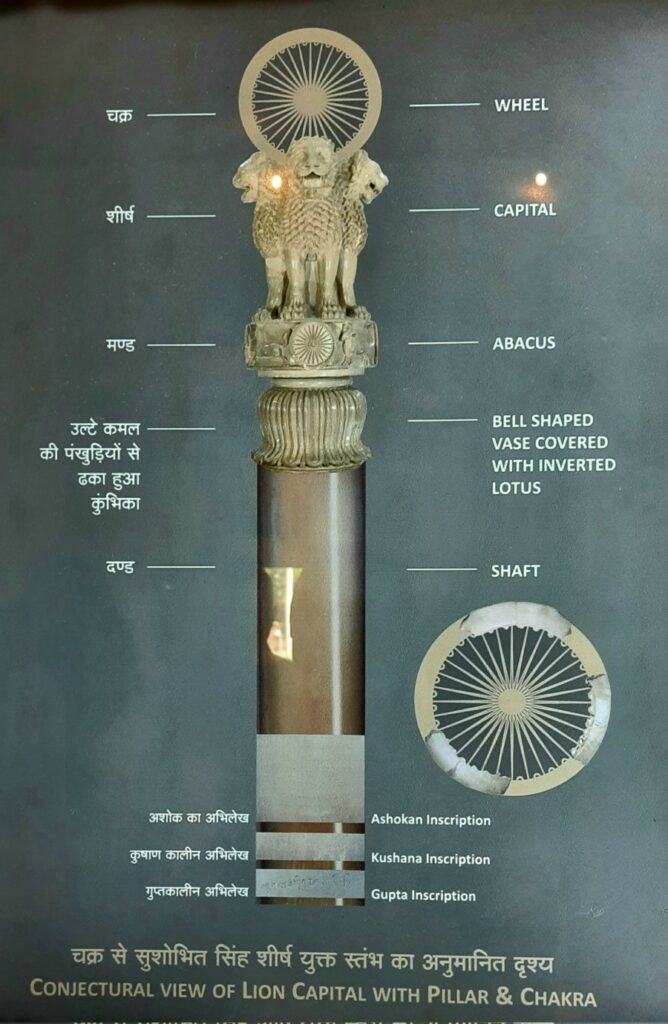

- Architecture: Mauryan pillars mainly comprise of four parts:

- Shaft: A long shaft formed the base and was made up of a single piece of stone or monolith.

- Capital: On top of shaft lay the capital, which was either lotus-shaped or bell-shaped.

- Abacus: Above the capital, there was a circular or rectangular base known as the abacus.

- Capital Figure: All the capital figures (usually animals like a bull, lion, elephant, etc) are vigorous and carved standing on a square or circular abacus.

Similarities with Persian (Achamenian) Pillars

- Polished Stones and Motifs : Both Maurya and Achaemenian pillars, used polished stones and have certain common sculpture motifs such as the lotus.

- Proclamations: Maurya’s idea of inscribing proclamations (related to Buddhist teachings and court orders) on pillars has its origin in Persian pillars.

- Third Person: Inscriptions of both empires begin in the third person and then move to the first person.

Differences with Persian (Achamenian) Pillars

- The Capital Figure: It was absent in Mauryan pillars of the Kumhrar hall whereas pillars at Persepolis have the elaborate capital figures.

- The Shape and Ornamentation: The shape of Mauryan lotus is different from the Persian pillar.

- Pillar Surface: Most of the Persian pillars have a fluted/ ridged surface while the Mauryan pillars have a smooth surface.

- Architectural Scheme: The Achaemenid pillars were generally part of some larger architectural scheme, and bit complex and complicated, while the Ashokan pillars were simple and independent freestanding monuments.

- Shaft: Unlike Mauryan shafts which are built of monolith (single piece of stone), Persian/Achaemenian shafts were built of separate segments of stones (aggregated one above the other).

Lion Capital, Sarnath

- The Lion Capital discovered more than a hundred years ago at Sarnath, near Varanasi, is generally referred as Sarnath Lion Capital.

- Hsuen Tsang: Mentions of a seventy-foot high pillar with shining polish standing at the same site.

- It is one of the finest examples of sculpture from Mauryan period and was built by Ashoka in commemoration of ‘Dhammachakrapravartana’ or the first sermon of Buddha.

- Originally it consists of five components:

- The pillar shaft.

- The lotus bell or base.

- A drum on the bell base with four animals proceeding clockwise (abacus).

- Figure of four majestic addorsed (back to back) lions

- The crowning element, Dharamchakra/Dharmachakra.

- Dharamchakra (the fifth component said above), a large wheel was also a part of this pillar. However, this wheel is lying in broken condition and is displayed in the site museum of Sarnath.

- The capital has four Asiatic lions seated back to back and their facial muscularity is very strong.

- They symbolize power, courage, pride and confidence.

- The surface of the sculpture is heavily polished, which is typical of the Mauryan period.

- Abacus (drum on the bell base) has the depiction of a chakra (wheel) in all four directions and a bull, a horse, an elephant and a lion between every chakra.

- Each chakra has 24 spokes in it.

- This 24 spoke chakra is adopted to the National Flag of India.

- The circular abacus is supported by an inverted lotus capital.

- The capital without the shaft, the lotus bell and crowning wheel has been adopted as the National Emblem of Independent India.

- In the emblem adopted by Madhav Sawhey, only three Lions are visible, the fourth being hidden from view. The abacus is also set in such a way that only one chakra can be seen in the middle, with the bull on the right and horse on the left.

- A lion capital has also been found at Sanchi, but is in a dilapidated condition.

- A pillar found at Vaishali is facing towards the north, which is the direction of Buddha’s last voyage.

Lauriya Nandangarh (Bihar)

- The top of the pillar is bell-shaped with a circular abacus.

- It has six edicts inscribed on its polished stone shaft.

- Situated on the trade route that connects the eastern Gangetic basin with western Asia.

- The lotus bell capital supports a drum carved with a row of geese. A seated lion crowns the capital.

- The pillar reveals the Achaemenid and Hellenistic influences on the Indian stone carving tradition.

- Emperor Ashoka commemorated the site of Lauriya Nandangarh with a Dhamma Stambhadorned with a single Lion Capital at the top.

Rampurva (Bull Capital) (Delhi)

- It is a realistic depiction of a Zebu bull.

- It is a mixture of Indian and Persian elements.

- The motifs on the base, atop the inverted lotus, the rosette, the palmette, and the acanthus ornaments are not Indian features.

- Rashtrapati Bhavan houses the magnificent sandstone capital.

Prayag -Prashasti (Allahabad Pillar) (Uttar Pradesh)

- It carries major pillar edicts from 1 to 6.

- It also contains the schism edict of Ashoka.

- Inscriptions of Gupta Emperor Samudragupta and Mughal Emperor Jehangir are also attributed to this pillar.

- The inscription mentions that Samudragupta defeated twelve rulers in his South India expedition.

Pillar Edicts and Inscriptions

- Ashoka’s 7 pillar edicts: These were found at Topra (Delhi), Meerut, Kausambhi, Rampurva, Champaran, Mehrauli:

- Pillar Edict I: Asoka’s principle of protection to people.

- Pillar Edict II: Defines Dhamma as the minimum of sins, many virtues, compassion, liberality, truthfulness, and purity.

- Pillar Edict III: Abolishes sins of harshness, cruelty, anger, pride, etc.

- Pillar Edict IV: Deals with duties of Rajukas.

- Pillar Edict V: List of animals and birds which should not be killed on some days and another list of animals which have not to be killed at all.

- Pillar Edict VI: Dhamma policy

- Pillar Edict VII: Works done by Asoka for Dhamma policy.

- Minor Pillar Inscriptions

- Rummindei Pillar Inscription: Asokha’s visit to Lumbini & exemption of Lumbini from tax.

- Nigalisagar Pillar Inscription, Nepal: It mentions that Asoka increased the height of stupa of Buddha Konakamana to its double size.

- Major Pillar Inscriptions

- Sarnath Lion Capital: Near Varanasi was built by Ashoka in commemoration of Dhammachakrapravartana or the first sermon of Buddha.

- Vaishali Pillar, Bihar, single lion, with no inscription.

- Sankissa Pillar, Uttar Pradesh

- Lauriya-Nandangarth, Champaran, Bihar.

- Lauriya-Araraj, Champaran, Bihar

- Allahabad pillar, Uttar Pradesh.

Stupas and Chaityas:

Stupa, chaitya and vihara are part of Buddhist and Jain monastic complex, but the largest number belongs to the Buddhist religion. One of the best examples of the structure of a stupa is in the third century B.C. at Bairat, Rajasthan. The Great Stupa at Sanchi was built with bricks during the time of Ashoka and later it was stone and many new additions were made. Subsequently, many such stupas were constructed which shows the popularity of Buddhism.

- From second century B.C. onwards, we get many inscriptional evidences mentioning donors and, at times, their profession.

- The pattern of patronage has been a very collective one and there are very few examples of royal patronage.

- Patrons range from lay devotees to gahapatis (householders, ordinary farmers, etc.) and kings.

- Donations by the guild are also mentioned at several places.

- There are very few inscriptions mentioning the names of artisans such as Kanha at Pitalkhora and his disciple Balaka at Kondane caves.

- Artisans’ categories like stone carvers, goldsmith, carpenters, etc. are also mentioned in the inscriptions.

- Traders recorded their donation along with their place of origin.

- In the subsequent century (mainly 2nd century B.C), stupas were elaborately built with certain additions like the enclosing of the circumbulatory path with railings and sculptural decorations.

- Stupa consisted of a cylindrical drum and a circular anda with a harmika and chhatra on the top which remains consistent throughout with minor variations and changes in shape and size.

- Gateways were also added in the later periods.

Construction of Stupa

- Stupa: Stupas were burial mounds prevalent in India from the vedic period.

- Architecture: Stupas consist of a cylindrical drum with a circular anda and a harmika and a chhatra on the top.

- Anda: Hemispherical mound symbolic of the mound of dirt used to cover Buddha’s remains (in many stupas actual relics were used).

- Harmika: Square railing on top of the mound.

- Chhatra: Central pillar supporting a triple umbrella form.

- Material Used: The core of the stupa was made of unburnt brick while the outer surface was made by using burnt bricks, which were then covered with a thick layer of plaster and medhi and the toran were decorated with wooden sculptures.

- Examples:

- Sanchi Stupa in Madhya Pradesh is the most famous of the Ashokan stupas.

- Piprahwa Stupa in Uttar Pradesh is the oldest one.

- Stupas built after the death of Buddha: Rajagriha, Vaishali, Kapilavastu, Allakappa, Ramagrama, Vethapida, Pava, Kushinagar and Pippalivana.

- Stupa at Bairat, Rajasthan: Grand stupa with a circular mound and a circumambulatory path.

- Architecture: Stupas consist of a cylindrical drum with a circular anda and a harmika and a chhatra on the top.

Sanchi Stupa (Madhya Pradesh)

- The great stupa at Sanchi was built with bricks during the time of Ashoka and later was covered with stones.

- It was enlarged using local sandstone during the Sunga period.

- The elaborately-carved gateways were added later (by Satvahanas) in the 1st century BC. It depicts Jataka stories.

- The main body of the stupa symbolises the cosmic mountain.

- It is topped by a ‘harmika’ to hold the triple umbrella, or ‘chhatraveli’, representing the three jewels of Buddhism – the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha.

- The reliefs of Sanchi display the following quite prominently.

- The four great events of the Buddha’s life– birth, attainment of knowledge, dharma chakra – pravartana and Mahaparinirvana.

- Representations of birds and animals like lions, elephants, camels, ox, etc., are abundant.

- Some animals are shown with riders in heavy coats and boots.

- Lotus and wishing vines and

- Unique representation of forest animals.

Bharhut Stupa (Madhya Pradesh)

- Originally built by Ashoka but enlarged later by Shungas.

- It is important for its sculptures.

- The important features:

- Gateways or toranas, which are imitations in stone of wooden gateways.

- Railings made of red sandstone spreading out from the gateways. They also are imitations, in stone, of post and rail fence, but the stone railings of Bharhut have, on top, a heavy stone border (coping).

- Railings have carvings of Yakshas, Yakshis and other divinities associated with Buddhism.

- There are, as in other Stupa railings, representations of Buddhist themes like Jataka stories in combination with various natural elements.

Dhauli Shanti Stupa (Orissa)

- Ashoka laid the foundation of Dhauligiri Shanti Stupa at a place known for the end of the Kalinga War.

- The overall structure is in the shape of a dome.

- The Dhauli Shanti Stupa has four massive idols of Lord Buddha in various postures, along with episodes from Gautam Buddha’s life carved on stone slabs.

Dhamek Stupa (Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh)

- Its construction was ordered by Emperor Ashoka.

- It is the exact spot of Buddha’s first sermon.

- At Dhamek stupa Buddha revealed an eight-fold path leading to nirvana.

- The site is described as Mriga-daya-vanam (sanctuary for animals).

DEPICTION OF BUDDHA IN CHAITYAS

- During the early period, Buddha is depicted symbolically through footprints, stupas, lotus throne, chakra, etc.

- Gradually narrative became a part.

- Thus, the events from life of Buddha, the Jataka stories, etc. were depicted on the railings and torans of the stupas.

- The main events associated with the Buddha’s life which were frequently depicted were events related to birth, renunciation, enlightment, dhammachakrapravartana (first sermon), and mahaparinirvana (death).

- Among Jataka stories that are frequently depicted are Chhadanta Jataka, Ruru Jataka, Sibi Jataka, Vidur Jataka, Vessantara Jataka and Shama Jataka.

Cave Architecture

- During the Mauryan period, caves were generally used as viharas, i.e. living quarters, by the Jain and Buddhist monks.

- Mauryan caves are highly polished. For example- Lomas Rishi cave.

- Example: The seven caves (Satgarva) in the Makhdumpur region of Jehanabad district, Bihar, were created by Mauryan emperor Ashoka for the Ajivika Sect:

- Four in Barabar Hill (Lomus Rishi, Sudama, Viswamitra and Karna Chopar Caves).

- Three in Nagarjuni Hill (Vahiyaka, Gopika and Vadathika Caves), were formed during the time of Dasharath, grandson of Ashoka.

- Some of the rock-cut chambers resemble the wooden buildings of that period. For example- It can be seen in the Lomus Rishi and Sudama caves of Barabar Hills.

- The facade of the Lomas Rishi cave is decorated with the semicircular chaitya arch as the entrance and interior hall are rectangular, with a circular chamber at the back.

Lomus Rishi Cave, Barabar Hills

- Rock-cut cave carved at Barabar Hills near Gaya in Bihar is known as Lomus Rishi Cave.

- It is patronized by Ashoka for Ajeevika sect.

- The facade of the cave is decorated with the semicircular Chaitya (worship place) arch as the entrance.

- An elephant frieze carved in high relief on the chaitya.

- The interior hall of this cave is rectangular with a circular chamber at the back.

- Entrance is located on the side wall of the hall.

Ajivika Sect

- It was founded by Goshala Maskariputra (a friend of Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism) and was contemporary of Jainism and Buddhism.

- Ajivika sect is based on the philosophy that the affairs of the entire universe were ordered by a cosmic force called niyati (Sanskrit: “rule” or “destiny”) that determined all events, including an individual’s fate.

Mauryan Popular Art

Apart from the court art or royal patronage, sculpture, and pottery took the expressions of art by individual effort.

Sculptures

- Two of the most famous sculptures of the Mauryan period are those of Yaksha and Yakshi.

- Large statues of Yakshas and Yakshinis are found at places like Patna, Vidisha and Mathura.

- They were objects of worship related to all three religions – Jainism, Hinduism, and Buddhism.

- The earliest mention of yakshi can be found in Silappadikaram, a Tamil text.

- The torso of the nude male figure found at Lohanipur at Patna.

- Didargunj Yakshi was found at Didargunj village at Patna.

Yakshas and Yakshinis

- Large statues of Yakshas and Yakshinis are found at many places like Patna, Vidisha and Mathura.

- They are mostly in the standing position.

- Their polished surface is distinguished element.

- Depiction of faces is in full round with pronounced cheeks and physiognomic detail.

- They show sensitivity towards depicting the human physique.

- Finest example is Yakshi figure from Didarganj, Patna.

DIDARGANJ YAKSHI

- The life-size standing image of a Yakshi holding a chauri (flywhisk) from Didarganj near Patna is another good example of the sculpture tradition of Mauryan period.

- It is a tall well proportioned, free standing sculpture in round made in sandstone with a polished surface.

- The chauri is held in the right hand, whereas the left hand is broken.

- The image shows sophistication in the treatment of form and medium.

- The sculpture’s sensitivity towards the round muscular body is clearly visible.

- The face is round, fleshy cheeks, while the neck is relatively small in proportion; the eyes, nose and lips are sharp.

- Folds of muscles are properly rendered.

- The necklace beads are in full round, hanging the belly.

- The tightening of garments around the belly rendered with great care.

- Every fold of the garments on the legs is shown by protruding lines clinging to the legs, which also creates a somewhat transparent effect.

- Thick bell ornaments adorn the feet.

- Heaviness in the torso is depicted by heavy breasts.

- The hair is tied in a knot at the back and the back is clear.

- Flywhisk in the right hand is shown with incised lines continued on the back of the image.

Dhauli Elephant (Orissa)

- Carved in the living rock.

- the Ashoka edict at the place ends with the word Sevto (white) in Pali. It suggests that it depicts Airavat, a white elephant depicted in Indian religious texts.

- Situated near the battlefield where Ashoka renounced violence and turned towards Buddhism.

Pottery

Pottery of the Mauryan period is generally referred to as Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW).

- Mauryan pottery was characterized by black paint and highly lustrous finish and was generally used as luxury items.

- Kosambi and Patliputra were the centers of NBPW pottery.

Significance

- Stupas were known in India before the time of Ashoka but when Ashoka divided up the existing body relics of the Buddha and erected monuments to enshrine them, the stupas became the objects of cult worship.

- The Stupas were solid domes constructed of brick or stone, varying in sizes. Samrat Ashoka built numerous stupas scattered over the country. But most of the stupas have not survived the ravages of time.

- The most striking monuments of Mauryan art are the celebrated Pillars of Dharma. These pillars were free-standing columns and were not used as supports to any structure. They had two main parts, the shaft and the capital. The shaft is a monolith column made of one piece of stone with exquisite polish. The art of polishing was so marvelous that many people felt that it was made of metal.

- The pillars are not the only artistic achievements of Ashoka’s reign. The rock-cut caves of Ashoka and that of his grandson Dasaratha Maurya constructed for the residence of monks are, wonderful specimens of art. The caves at Barabar hill in the north of Gaya and the Nagarjuna hill caves, the Sudama caves, etc. are the extant remains of cave architecture of the Mauryan era.

- The Sarnath column has the most magnificent capital. It is a product of a developed type of art of which the world knew in the Third Century B.C. It has been fittingly adopted as the emblem of the Modem Indian Republic. It is seven feet in height. The lowest part of the capitol is curved as an inverted lotus and bell-shaped. Above it are four animals, an elephant, a horse, a bull, a lion representing the east, south, west, and north in Vedic symbol.

- The gilded pillars of the Mauryan palace were adorned with golden vines and silver birds. The workmanship of the imperial palace was of very high standard.

- Chinese traveler Fa-Hien stated that “Ashoka’s palace was made by spirits” and that its carvings are so elegantly executed “which no human hands of this world could accomplish”

- The Mauryan pottery consisted of many types of wares. The black polished type found in North India is important. It has a burnished and glazed surface.

- The life-size standing image of a Yakshini holding a chauri (fly whisk) from Didarganj near modern Patna is one of the finest examples of the sculptural tradition of the Mauryan Period – Made of sandstone. Distinguishing elements in all these images was its highly polished surface

- Mauryan art and architecture depicted the influence of Persians and Greeks. During the reign of Ashoka, many monolithic stone pillars were erected on which teachings of ‘Dhamma’ were inscribed.

The art and architecture of this period was progressive, liberal and secular in nature. The value of stupa at sanchi and bull capital at sarnath depict the greatness and stand as testimony to this golden period of Indian history. Hence it can be said that the art and architecture of the Mauryan Empire constitutes the culminating point of the progress of Indian art.

Also refer :