Land tenure Systems

Land tenure refers to the possession or holding (tenere=to hold, Latin) of the many rights and responsibilities associated with a parcel of land.

These rights may include

- the right of access to the land,

- the right to control products from the land (e.g., trees),

- the right of succession,

- the right of transfer

- and the right to determine changes in land use.

Importantly, land tenure also encompasses obligations to maintain the land. Land tenure arrangements may be formal (i.e., recognized by the state) or informal (i.e., traditional or customary).

At its simplest, there are four general categories of land tenure institutions operating in the world today: customary land tenure, private ownership, tenancy, and state ownership. These categories exist in at least four general economic contexts: feudal, traditional communal, market economy, and socialist economy.

land tenure systems existed in pre-independent India

The Zamindari system

- Zamindari System (also known as Permanent Settlement System) was introduced by Cornwallis in 1793 through Permanent Settlement Act.

- It was introduced in provinces of Bengal, Bihar, Orissa and Varanasi. Zamindars were recognized as owner of the lands.

- Zamindars were given the rights to collect the rent from the peasants.

- The realized amount would be divided into 11 parts. 1/11th of the share belonged to Zamindars and 10/11th of the share belonged to East India Company

The Mahalwari system

- Mahalwari system was introduced in 1833 during the period of William Bentick.

- It was introduced in Central Province, North-West Frontier, Agra, Punjab, Gangetic Valley, etc of British India.

- The Mahalwari system included many provisions of both the Zamindari System and Ryotwari System.

- In this system, the land was divided into Mahals. Each Mahal comprises one or more villages.

- Ownership rights were vested with the peasants.

- The villages committee was held responsible for collection of the taxes.

The Ryotwari system

- Here, individual cultivator was supposed to pay the rent directly to the government without any intermediary. It was prevalent in parts of Madras, Bombay province and Assam.

- In practice, however, all three types of system had taken the features of each other. The picture that emerged at independence was that of exploitation of agricultural labourers at the hands of landlords, exorbitant rents, lack of incentive for technological progress and rigid system of land transfer across the country.

Land reforms

- Land reform involves the changing of laws, regulations or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural land.

- Land reform can, therefore, refer to transfer of ownership from the more powerful to the less powerful, such as from a relatively small number of wealthy (or noble) owners with extensive land holdings (e.g., plantations, large ranches, or agribusiness plots) to individual ownership by those who work the land. Such transfers of ownership may be with or without compensation; compensation may vary from token amounts to the full value of the land.

- The common characteristic of all land reforms, however, is modification or replacement of existing institutional arrangements governing possession and use of land.

- Land distribution has been part of India’s state policy from the very beginning. Independent India’s most revolutionary land policy was perhaps the abolition of the Zamindari system (feudal land holding practices). Land-reform policy in India had two specific objectives:

- To remove such impediments to increase in agricultural production as arise from the agrarian structure inherited from the past.

- To eliminate all elements of exploitation and social injustice within the agrarian system, to provide security for the tiller of soil and assure equality of status and opportunity to all sections of the rural population.

Land-Reforms Pre Independence

- Under the British Raj, the farmers did not have the ownership of the lands they cultivated, the landlordship of the land lied with the Zamindars, Jagirdars etc.

- Several important issues confronted the government and stood as a challenge in front of independent India.

- Land was concentrated in the hands of a few and there was a proliferation of intermediaries who had no vested interest in self-cultivation.

- Leasing out land was a common practice.

- The tenancy contracts were expropriative in nature and tenant exploitation was almost everywhere.

- Land records were in extremely bad shape giving rise to a mass of litigation.

- One problem of agriculture was that the land was fragmented into very small parts for commercial farming.

- It resulted in inefficient use of soil, capital, and labour in the form of boundary lands and boundary disputes.

Land-reforms after independence

- A committee, under the Chairmanship of J. C. Kumarappan was appointed to look into the problem of land. The Kumarappa Committee’s report recommended comprehensive agrarian reform measures.

- The Land Reforms of the independent India had four components:

- The Abolition of the Intermediaries

- Tenancy Reforms

- Fixing Ceilings on Landholdings

- Consolidation of Landholdings.

- These were taken in phases because of the need to establish a political will for their wider acceptance of these reforms.

Four Phases of Land Reforms

- The first and longest phase (1950 – 72) consisted of land reforms that included three major efforts: abolition of the intermediaries, tenancy reform, and the redistribution of land using land ceilings. The abolition of intermediaries was relatively successful, but tenancy reform and land ceilings met with less success.

- The second phase (1972 – 85) shifted attention to bringing uncultivated land under cultivation.

- The third phase (1985 – 95) increased attention towards water and soil conservation through the Watershed Development, Drought-Prone Area Development (DPAP) and Desert-Area Development Programmes (DADP). A central government Waste land Development Agency was established to focus on wasteland and degraded land. Some of the land policy from this phase continued beyond its final year.

- The fourth and current phase of policy (1995 onwards) centres on debates about the necessity to continue with land legislation and efforts to improve land revenue administration and, in particular, clarity in land records.

Components of Land Reforms

- Abolition of Intermediaries like Zamindars or jagirdars so that ownership of land could be clearly identified with management and control. Many states promulgated laws to put an end to absentee landlordism and as a result about 30 lakh tenants acquired land ownership over an area of 62 lakh acres throughout the country.

- Tenancy reforms to confirm the rights of occupancy of tenants and to regulate rent of leased land. The rent paid by the tenants during the pre-independence period was exorbitant; between 35% and 75% of gross produce throughout India. These reforms could not be implemented due to two main reasons. Many small tenants were forced to surrender their land under the so called “voluntary surrender” rule in the legislation. Secondly, the unavailability of accurate and up-to-date land record also constrained its implementation.

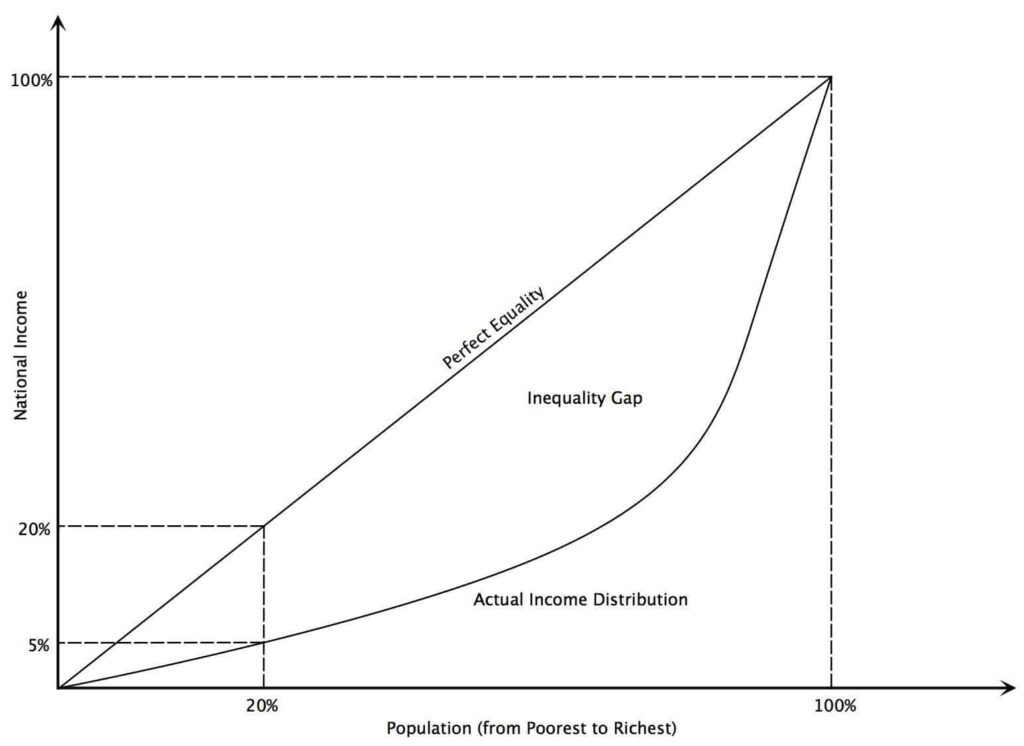

- Reorganization of land holdings to offset extremely uneven distribution of agricultural land. In 1942 the Kumarappan Committee recommended the maximum size of lands a landlord can retain. It was three times the economic holding i.e. sufficient livelihood for a family.

- By 1961-62, all the state governments had passed the land ceiling acts. But the ceiling limits varied from state to state.

- To bring uniformity across states, a new land ceiling policy was evolved in 1971.In 1972, national guidelines were issued with ceiling limits varying from region to region, depending on the kind of land, its productivity, and other such factors.

- It was 10-18 acres for best land, 18-27 acres for second class land and for the rest with 27-54 acres of land with a slightly higher limit in the hill and desert areas. Under this, ceiling laws were imposed which laid down the maximum land that can be owned by a land holder (which was subsequently amended to holding by a family with effect from 1972). The excess land was to be surrendered to the government.

- But its performance remained dismal as it lead to redistribution of less than 2% of operated area by 1992. Thus, with the exception of abolition of intermediaries, other reforms could not be implemented mainly due to lack of political will.

- Consolidation of holding was introduced as a measure of improving farming efficiency. Consolidation referred to reorganization/redistribution of fragmented lands into one plot. It made considerable progress in Punjab, Haryana and western U.P. but did not took off in southern and eastern states.

- Cooperative joint farming, recommended by the Congress Agrarian Reforms Committee under Mr. J. C. Kumarappa was also encouraged in the five year plans initially. Under this, farmers pool their land and reap the economies of scale, although the ownership continues to remain with the individual farmer. But this could not be implemented mainly because of farmers’ reluctance to alienate their land. Many landlords also tried to misuse this concept to circumvent land ceiling.

- The National Land Records Modernization Programme (NLRMP) was launched by the Government of India in August 2008, aimed to modernize management of land records, minimize scope of land/ property disputes, enhance transparency in the land records maintenance system, and facilitate moving eventually towards guaranteed conclusive titles to immovable properties in the country.

Reasons for Failure of Land Reforms:

Out of the many reasons forwarded by the experts responsible for the failure of the land reforms in India, the following three could be considered the most important ones:

- Deficiency of Reliable Records : The absence of concurrent evaluation and reliable (up-to-date) records is the biggest hurdle for the slow progress of land reforms.

- Lack of integrated approach such as abolition of intermediary tenures, tenancy reforms and ceiling of holdings etc.

- Land in India is considered a symbol of social prestige, status and identity unlike the other economies which succeeded in their land reform programmes, where it is seen as just an economic asset for income earning.

- Lack of political wills which was required to affect land reforms and make it a successful programme.

- Rampant corruption in public life, political hypocricy and leadership failure in the Indian democratic system.

Also refer :