The Revolt OF 1857

The Indian Mutiny of 1857 was a widespread but unsuccessful rebellion against the rule of the British East India Company in India which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British crown. The revolt, for long mistaken to be a mere mutiny of the Indian sepoys in the Bengal army were indeed joined by an aggrieved rural society of north India. Its causes, therefore, need to be searched for not only in the disaffection of the army, but in a long-drawn process of fundamental social and economic change that upset the peasant communities during the first century of the Company’s rule.

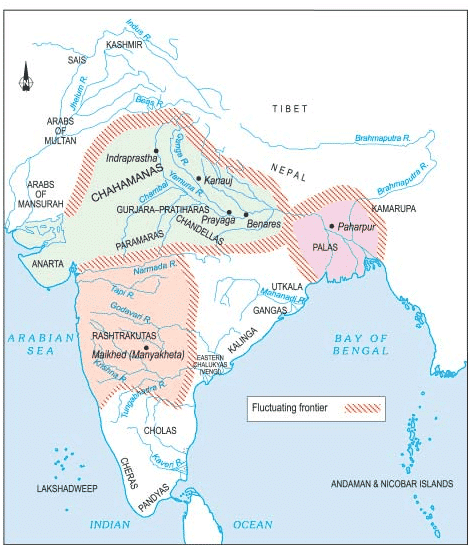

First of all, regions and people who were beneficiaries of colonial rule did not revolt. Bengal and Punjab remained peaceful; the entire south India remained unaffected too. On the other hand, those who revolted had two elements among them-the feudal elements and the big landlords on the one end and the peasantry on the other.

Different classes had different grievances and the nature of grievances also varied from region to region. So far as the feudal elements were concerned, their major grievance was against the annexations under Lord Dalhousie’s ‘Doctrine of Lapse’ which derecognised the adopted sons of the deceased princes as legal heirs and their kingdoms were annexed.

In this way, Satara (1848), Nagpur, Sambalpur and Baghat (1850), Udaipur (1852) and Jhansi (1853) were taken over in quick succession. This amounted to British interference in the traditional system of inheritance and created a group of disgruntled feudal lords who had every reason to join the ranks of the rebels.

Finally, in February 1856 Awadh was annexed and the king was deported to Calcutta. The annexation did not merely affect the nawab and his family, but the entire aristocracy attached to the royal court. These deposed princes in many cases offered leadership to the rebels in their respective regions and thus provided legitimacy to the revolt.

Thus, Nana Sahib, the adopted son of Peshwa Baji Rao II, assumed leadership in Kanpur, Begum Hazrat Mahal took control over Lucknow, Khan Bahadur Khan in Rohilkhand, and Rani Lakshmibai appeared as the leader of the sepoys in Jhansi, although earlier she was prepared to accept British hegemony if her adopted son was recognised as the legitimate heir to the throne. In other areas of central India, where there was no such dispossession, like Indore, Gwalior, Saugar or parts of Rajasthan, where the sepoys rebelled, the princes remained loyal to the British.

Causes of The Revolt OF 1857

Political Cause

- The British policy of expansion: The political causes of the revolt were the British policy of expansion through the Doctrine of Lapse and direct annexation.

- A large number of Indian rulers and chiefs were dislodged, thus arousing fear in the minds of other ruling families who apprehended a similar fate.

- Rani Lakshmi Bai’s adopted son was not permitted to sit on the throne of Jhansi.

- Satara, Nagpur and Jhansi were annexed under the Doctrine of Lapse.

- Jaitpur, Sambalpur and Udaipur were also annexed.

- The annexation of Awadh by Lord Dalhousie on the pretext of maladministration left thousands of nobles, officials, retainers and soldiers jobless. This measure converted Awadh, a loyal state, into a hotbed of discontent and intrigue.

Social and Religious Cause

- The rapidly spreading Western Civilisation in India was an alarming concern all over the country.

- An act in 1850 changed the Hindu law of inheritance enabling a Hindu who had converted to Christianity to inherit his ancestral properties.

- The people were convinced that the Government was planning to convert Indians to Christianity.

- The abolition of practices like sati and female infanticide, and the legislation legalizing widow remarriage, was believed as threats to the established social structure.

- Introducing Western methods of education was directly challenging the orthodoxy for Hindus as well as Muslims

- Even the introduction of the railways and telegraph was viewed with suspicion.

Economic Cause

- The colonial policies of the East India Company destroyed the traditional economic fabric of the Indian society. The peasantry were never really to recover from the disabilities imposed by the new and a highly unpopular revenue settlement.

- Impoverished by heavy taxation, the peasants resorted to loans from money-lenders/traders at usurious rates, the latter often evicting the former from their land on non-payment of debt dues.

- British policy discouraged Indian handicrafts and promoted British goods. The highly skilled Indian craftsmen were forced to look for alternate sources of employment that hardly existed, as the destruction of Indian handicrafts was not accompanied by the development of modern industries.

- Zamindars, the traditional landed aristocracy, often saw their land rights forfeited with frequent use of a quo warranto by the administration. This resulted in a loss of status for them in the villages. In Awadh, the storm centre of the revolt, 21,000 taluqdars had their estates confiscated and suddenly found themselves without a source of income, “unable to work, ashamed to beg, condemned to penury”.

- The ruin of Indian industry increased the pressure on agriculture and land, which could not support all the people.

Military Causes

- The Revolt of 1857 began as a sepoy mutiny:

- Indian sepoys formed more than 87% of the British troops in India but were considered inferior to British soldiers.

- An Indian sepoy was paid less than a European sepoy of the same rank.

- A more immediate cause of the sepoys’ dissatisfaction was the order that they would not be given the foreign service allowance (bhatta) when serving in Sindh or in Punjab.

- The annexation of Awadh, home of many of the sepoys, further inflamed their feelings.

- They were required to serve in areas far away from their homes.

- In 1856 Lord Canning issued the General Services Enlistment Act which required that the sepoys must be ready to serve even in British land across the sea. To the religious Hindu of the time, crossing the seas meant loss of caste.

Immediate Cause

- The Revolt of 1857 eventually broke out over the incident of greased cartridges.

- A rumour spread that the cartridges of the new enfield rifles were greased with the fat of cows and pigs.

- Before loading these rifles the sepoys had to bite off the paper on the cartridges.

- Both Hindu and Muslim sepoys refused to use them.

- Lord Canning tried to make amends for the error and the offending cartridges were withdrawn but the damage had already been done. There was unrest in several places. The greased cartridges did not create a new cause of discontent in the Army, but supplied the occasion for the simmering discontent to come out in the open.

- In March 1857, Mangal Pandey, a sepoy in Barrackpore, had refused to use the cartridge and attacked his senior officers.

- He was hanged to death on 8th April.

- On 9th May, 85 soldiers in Meerut refused to use the new rifle and were sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment.

Centres of The Revolt OF 1857

The revolt spread over the entire area from the neighbourhood of Patna to the borders of Rajasthan. The main centres of revolt in these regions namely Delhi, Kanpur, Lucknow, Bareilly, Jhansi, Gwalior and Arrah in Bihar.

Delhi

At Delhi, the nominal and symbolic leadership belonged to the Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah, but the real command lay with a court of soldiers headed by General Bakht Khan who had led the revolt of Bareilly troops and brought them to Delhi.

Lucknow

It was the capital of Awadh. Begum Hazrat Mahal, one of the begums of the ex-king of Awadh, took up the leadership of the revolt. Her son, Birjis Qadir, was proclaimed the nawab and a regular administration was organised with important offices shared equally by Muslims and Hindus.

Kanpur

The revolt was led by Nana Saheb, the adopted son of Peshwa Baji Rao II. He joined the revolt primarily because he was deprived of his pension by the British and banished from Poona, and was living near Kanpur. Nana Saheb expelled the English from Kanpur, proclaimed himself the Peshwa, acknowledged Bahadur Shah as the Emperor of India and declared himself to be his governor.

Sir Hugh Wheeler, commanding the station, surrendered on June 27, 1857, and was killed on the same day. The victory was short-lived. Kanpur was recaptured by the British after fresh reinforcements arrived. The revolt was suppressed with terrible vengeance.

Nana Saheb escaped to Nepal but his brilliant commander Tantia Tope continued the struggle. Tantia Tope was finally defeated, arrested and hanged.

Jhansi

The most outstanding leader of the revolt was Rani Laxmibai, who assumed the leadership of the sepoys at Jhansi. Lord Dalhousie, the governor-general, had refused to allow her adopted son to succeed to the throne after her husband Raja Gangadhar Rao died, and had annexed the state by the application of the infamous ‘Doctrine of Lapse’. She was joined by Tantia Tope, a close associate of Nana Saheb, after the loss of Kanpur. The Rani of Jhansi and Tantia Tope marched towards Gwalior where they were hailed by the Indian soldiers. The Sindhia, the local ruler, however, decided to side with the English and took shelter at Agra. Gwalior was recaptured by the English in June 1858.

Bihar

The revolt was led by Kunwar Singh who belonged to a royal house of Jagdispur, Bihar.

Faizabad

Maulvi Ahmadullah of Faizabad was another outstanding leader of the revolt. He was a native of Madras and had moved to Faizabad in the north where he fought a stiff battle against the British troops. He emerged as one of the revolt’s acknowledged leaders once it broke out in Awadh in May 1857.

Bareilly

At Bareilly, Khan Bahadur, a descendant of the former ruler of Rohilkhand, was placed in command. Not enthusiastic about the pension being granted by the British, he organised an army of 40,000 soldiers and offered stiff resistance to the British.

Suppression and The Revolt OF 1857

- The revolt was finally suppressed. The British captured Delhi on September 20, 1857, after prolonged and bitter fighting. John Nicholson, the leader of the siege, was badly wounded and later succumbed to his injuries. Bahadur Shah was taken prisoner. The royal princes were captured and butchered on the spot, publicly shot at point-blank range by Lieutenant Hudson himself. The emperor was exiled to Rangoon where he died in 1862. Thus the great House of Mughals was finally and completely extinguished. A terrible vengeance was wreaked on the inhabitants of Delhi. With the fall of Delhi, the focal point of the revolt disappeared.

- Military operations for the recapture of Kanpur were closely associated with the recovery of Lucknow. Sir Colin Campbell occupied Kanpur on December 6, 1857. Nana Saheb, defeated at Kanpur, escaped to Nepal in early 1859, never to be heard of again. His close associate Tantia Tope escaped into the jungles of central India, but was captured while asleep in April 1859 and put to death.

- The Rani of Jhansi had died on the battlefield earlier in June 1858. Jhansi was recaptured by Sir Hugh Rose. By 1859, Kunwar Singh, Bakht Khan, Khan Bahadur Khan of Bareilly, Rao Sahib (brother of Nana Saheb) and Maulvi Ahmadullah were all dead, while the Begum of Awadh was compelled to hide in Nepal.

- By the end of 1859, British authority over India was fully re-established. The British government had to pour immense supplies of men, money and arms into the country, though the Indians had to later repay the entire cost through their own suppression.

| Places of Revolt | Indian Leaders | British Officials who suppressed the revolt |

| Delhi | Bahadur Shah II | John Nicholson |

| Lucknow | Begum Hazrat Mahal | Henry Lawrence |

| Kanpur | Nana Saheb | Sir Colin Campbell |

| Jhansi & Gwalior | Lakshmi Bai & Tantia Tope | General Hugh Rose |

| Bareilly | Khan Bahadur Khan | Sir Colin Campbell |

| Allahabad and Banaras | Maulvi Liyakat Ali | Colonel Oncell |

| Bihar | Kunwar Singh | William Taylor |

Why did the Revolt OF 1857 Fail?

All-India participation was absent

The eastern, southern and western parts of India remained more or less unaffected. This was probably because the earlier uprisings in those regions had been brutally suppressed by the Company.

All classes did not join

Certain classes and groups did not join and, in fact, worked against the revolt. Big zamindars acted as “break-waters to storm”; even Awadh taluqdars backed off once promises of land restitution were spelt out. Money lenders and merchants suffered the wrath of the mutineers badly and anyway saw their class interests better protected under British patronage.

Educated Indians viewed this revolt as backwards-looking, supportive of the feudal order and as a reaction of traditional conservative forces to modernity; these people had high hopes that the British would usher in an era of modernisation. Most Indian rulers refused to join and often gave active help to the British. Rulers who did not participate included the Sindhia of Gwalior, the Holkar of Indore, the rulers of Patiala, Sindh and other Sikh chieftains and the Maharaja of Kashmir. Indeed, by one estimate, not more than one-fourth

of the total area and not more than one-tenth of the total population was affected.

Poor Arms and Equipment

The Indian soldiers were poorly equipped materially, fighting generally with swords and spears and very few guns and muskets. On the other hand, the European soldiers were equipped with the latest weapons of war like the Enfield rifle. The electric telegraph kept the commander-in-chief informed about the movements and strategy of the rebels.

Uncoordinated and Poorly Organised

The revolt was poorly organised with no coordination or central leadership. The principal rebel leaders—Nana Saheb, Tantia Tope, Kunwar Singh, Laxmibai—were no match to their British opponents in generalship. On the other hand, the East India Company was fortunate in having the services of men of exceptional abilities in the Lawrence brothers, John Nicholson, James Outram, Henry Havelock, etc.

No Unified Ideology

The mutineers lacked a clear understanding of colonial rule; nor did they have a forward looking programme, a coherent ideology, a political perspective or a societal alternative. The rebels represented diverse elements with differing grievances and concepts of current politics.

**The mutiny mainly affected the Bengal army; the Madras and the Bombay regiments remained quiet, while the Punjabi and Gurkha

soldiers actually helped to suppress the rebellion.

Results of The Revolt OF 1857

- End of company rule: the great uprising of 1857 was an important landmark in the history of modern India.

- The revolt marked the end of the East India Company’s rule in India.

- Direct rule of the British Crown: India now came under the direct rule of the British Crown.

- This was announced by Lord Canning at a Durbar in Allahabad in a proclamation issued on 1 November 1858 in the name of the Queen.

- The Indian administration was taken over by Queen Victoria, which, in effect, meant the British Parliament.

- The India office was created to handle the governance and the administration of the country.

- Religious tolerance: it was promised and due attention was paid to the customs and traditions of India.

- Administrative change: the Governor General’s office was replaced by that of the Viceroy.

- The rights of Indian rulers were recognised.

- The Doctrine of Lapse was abolished.

- The right to adopt sons as legal heirs was accepted.

- Military reorganisation: the ratio of British officers to Indian soldiers increased but the armoury remained in the hands of the English. It was arranged to end the dominance of the Bengal army.

Conclusion

The revolt of 1857 was an unprecedented event in the history of British rule in India. It united, though in a limited way, many sections of Indian society for a common cause. Though the revolt failed to achieve the desired goal, it sowed the seeds of Indian nationalism.

Books written on the Revolt of 1857

- The Indian War of Independence by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar

- Rebellion, 1857: A Symposium by Puran Chand Joshi

- The Indian Mutiny of 1857 by George Bruce Malleson

- Great Mutiny by Christopher Hibbert

- Religion and Ideology of the Rebels of 1857 by Iqbal Hussain

- Excavation of Truth: Unsung Heroes of 1857 War of Independence by Khan Mohammad Sadiq Khan

Also, refer:

- Indian National Congress Sessions

- Important Social Reforms Acts Of British India

- 20 Lesser-Known Indian Freedom Fighters

- August Offer| Cripps Mission| C R Formula| Wavel Plan| Cabinet Mission| Mountbatten Plan

- Important Books And Authors Of India

- Indian Independence Movement| Top 25 Important MCQs

- Indian National Congress Sessions Before Independence

- Download the pdf of Important MCQs From the History Of Ancient India

- भारतीय राष्ट्रीय आंदोलन के महत्वपूर्ण व्यक्तित्व

- Difference Between Non-Co-Operation Movement And Civil Disobedience Movement

- Indian Independence Movement| Top 25 Important MCQs

- Important Battles/Wars Of India

- 20 Lesser-Known Indian Freedom Fighters

- Governors-General And Viceroys Of India